Studies for masters: new research into old master drawings

The Baillieu Library Print Collection includes approximately 100 drawings, many of them donated by Dr J. Orde Poynton in 1959.

In recent years a series of detailed research projects, undertaken through the university’s Cultural Collections Projects Program, have shone a spotlight upon these works.

Many of the drawings are studies, some by artists perfecting their skills, others created as patterns for prints, paintings or sculptures. They have been executed in various artistic styles and media and range in date from the 16th to the 19th centuries. They have passed through the hands of numerous artists, dealers and collectors before reaching their destination at the University of Melbourne. Some of their secrets and stories remain untold.Their beguiling lines and mysteries invite the viewer to explore beyond the marks that lie on the surface—to plumb their depths for some fascinating surprises.

A selection of drawings are on display on the ground floor, Baillieu Library form 6 June – 24 July 2016.

Selected drawings

Francesco Zuccarelli’s oil sketch is a curious image, and is unlike the majority of the works he produced. He is more commonly associated with rococo decorative painting. The focus

on the figure rather than the surrounding landscape makes this work a rare composition. The inscription on the verso states that it is from a series of ‘6 original drawings, with engravings’.

The Baillieu Library also holds a copy of the corresponding engraving by Antonio Baratta.

Francesco Zuccarelli, La Carità (Charity), c. 1760–70, gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton, 1959, Baillieu Library Print Collection University of Melbourne.

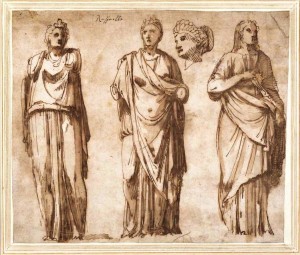

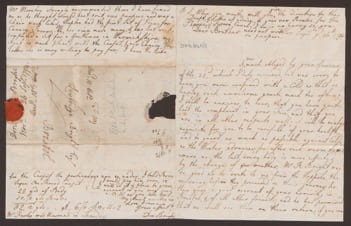

This mysterious mannerist drawing is a study of what appear to be one Juno and two Sabina statues. The drawing was probably executed in late 16th-century Rome, where all three statues were on public display. The drawing bears the monogram of renowned English collector John Barnard, as well as that of the lesser-known E.A. Patterson.

Unknown artist, Three statues of women and a study of a female head, c. 1580, gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton, 1959, Baillieu Library Print Collection University of Melbourne.

A handwritten inscription on the verso of this drawing reveals a name: ‘Antonÿ Georgetti’. This identified the sculptor of the statue after which the drawing was made: one of the

ten stone angels holding the Arma Christi (‘Weapons of Christ’) that adorn the Ponte Sant’ Angelo in Rome. According to the Bible, a sponge dipped in gall and vinegar

was offered to Jesus on the Cross, as a final act of persecution.

Unknown artist after Antonio Giorgetti, Angel with the sponge, 17th century, gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton, 1959, Baillieu Library Print Collection University of Melbourne.

This study, which represents a scene in the life of the infant St John the Baptist, can be paired with a more advanced composition drawing held in the Louvre, also attributed to Eustache Le Sueur. An artist of immense popularity in the 18th and 19th centuries, and one of the founders of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, Le Sueur was often referred to as ‘The French Raphael’, as is inscribed on the verso of this drawing.

Attributed to Eustache Le Sueur, Zechariah regains his speech,17th century, gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton, 1959, Baillieu Library Print Collection University of Melbourne.

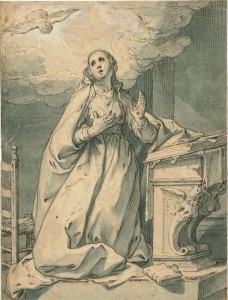

Abraham Bloemaert’s drawing is a preparatory design for a print which is titled The Annunciation. Another preparatory drawing of the same subject is held in Rotterdam. Bloemaert was a foremost Catholic artist whose voluminous output has endured for centuries.

Abraham Bloemaert, The Annunciation c.1625-35, gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton, 1959, Baillieu Library Print Collection University of Melbourne.

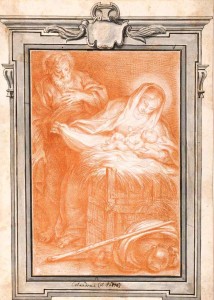

This drawing is very similar in technique and composition to that of Mary with the infant Christ In The Crib or Holy Family, another drawing which is in Düsseldorf and is a study for an unidentified painting. Giacinto Calandrucci moved to Rome to undertake training under Carlo Maratta.

Giacinto Calandrucci, Madonna with the Infant (c.1670), gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton, 1959, Baillieu Library Print Collection University of Melbourne.

Contributors

Alex Shapley, James Dear, Jessica Cole, Callum Reid, Peter Mitchelson and Fleur McArthur.