Integrating translation technology in the classroom: An interview with Professor Anthony Pym

Juerong Qiu

Various technologies and systems can be used to enhance human translation. In recent years, universities have started to include translation technologies in their curricula and have gained experience in teaching them. Here we explore the challenges of how to teach translation technology more effectively with Professor Anthony Pym.

Juerong Qiu: As far as I know, Translation Technologies, a course focusing on technologies related to translation, was not available until 2020. What made you decide to offer this subject to students studying translation and languages?

Anthony Pym: The original Master of Translation at the University of Melbourne had no technologies in it when I arrived in 2017, which was surprising because from 2016 we have had neural machine translation. This has significantly improved the quality of machine translation, making it a resource that professional translators should very much be aware of, even if they decide not to use it. So my first impulse was to show students what machine translation is these days and how they can work with it.

Juerong: It seems that students from different courses, such as Applied Linguistics, can also enrol in this subject.

Anthony: That’s right. I’m happy to make it available to anybody doing postgraduate studies.

In the Master of Applied Linguistics, we have lots of students who are training to be language teachers and doing research on that. Machine translation is being used by many language students at many levels. It’s a technology of extreme interest to language learning, as well as to translation.

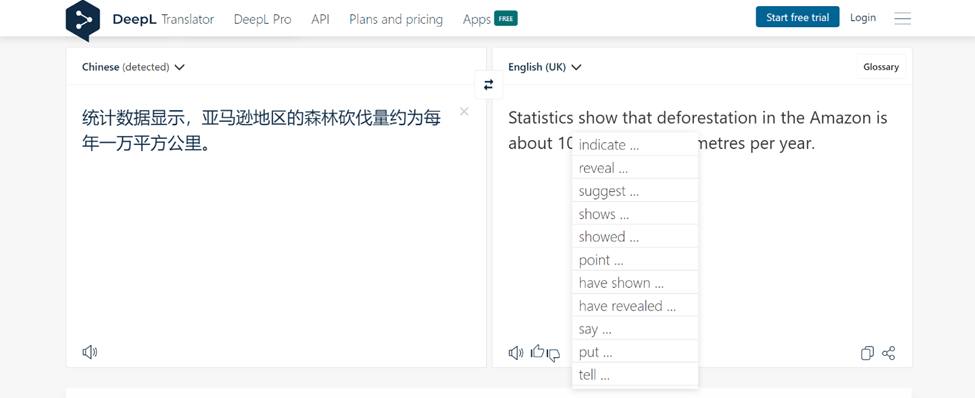

I hasten to point out here that people previously criticised machine translation for giving erroneous options, making students think that the erroneous translation was good in the target language. A lot of those problems have been overcome by tools like DeepL, where students can play with the start language, changing expressions and seeing how that’s translated and the student then clicks on the suggestions for the target language, gets a range of options, selects one and then sees how the rest of the sentence is adjusted. This becomes a great learning tool for adult language learners.

I think it’s good for people in Applied Linguistics to be aware of what’s out there. It remains of great interest for both translation and language teaching.

Juerong: What translation technologies do you cover in class to help students to learn different skills?

Anthony: First, we look at the current state of machine translation, just to give them an overview of the quality. I don’t insist too much that they understand the mechanics of neural machine translation, but they should be aware of where we are in the history of machine translation.

Then we look at post-editing. That means how to correct machine translation and identify the typical mistakes it makes. We use reverse engineering to discover why the machine is making mistakes. That helps us know what to look for and how to correct it.

We then look at pre-editing. That means changing the text so that it goes through machine translation easily and avoids mistakes early on. It teaches the principles of clear technical writing, sometimes going back to the rules of Basic English. That’s valuable – not just how to write for machine translation but also how to write very clearly in any technical context. It is a skill that is much needed.

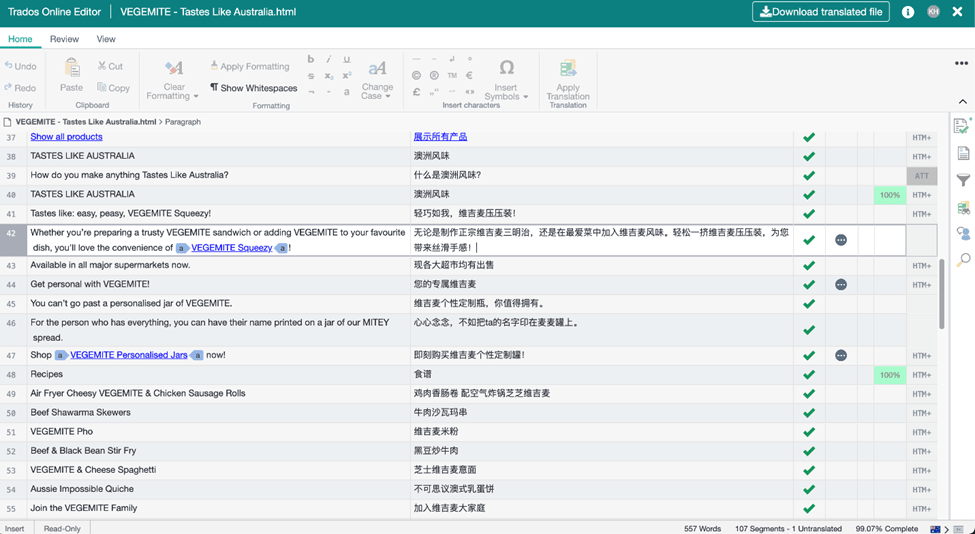

After that, we move on to translation memory suites, which are systems that enable the translator to retrieve and modify their previous translations — so you never have to translate the same sentence twice. We first use simple free ones that people can play with, like MateCat or Wordfast. Both of those are web-based. Then we move on to Trados, although next year I’ll be using both Phrase and Trados. Those are professional translation memory suites that incorporate lots of project management tools and terminology management tools.

At the end of that level, we’re up to professional-standard translation technology. We then have a final group project where students form translation companies and have to compete with each other to win a fictitious contract by showing and explaining the technology. Other students are client companies who have to decide who gets the contract. So it’s not just a question of using the technologies. You also have to know how to explain them to clients.

Juerong: Why do you introduce Trados and Phrase in particular?

Anthony: First, we would like to thank Phrase and Trados for granting us free access to their platforms through the Phrase Academic Edition and Trados Live. Importantly, they have web-based versions now, so we don’t have the problem of operating system incompatibility. For example, although Trados Live is not as complete as Trados Studio, which is desktop-based, it’s good enough for doing projects in class.

Juerong: What are the difficulties you encounter when teaching students to learn these two systems?

Anthony: Firstly, students are quite happy to learn the free online translation memory suites, particularly MateCat because it’s user-friendly and looks attractive. It has features like speech-to-text so you can speak your translation. So up to that point, there’s very little resistance among students — they’re quite happy to use it and play with it.

I don’t tell anybody what technology they have to use to do their translations. We do experiments. We can have half a group, using machine translation and doing post-editing, and the other half does fully human translation with no special technology. Then we compare the two. Students can figure out the results for themselves.

Among first-year students especially, they still don’t want to use translation technologies, even though you can show them that they go faster, and they do just as well, sometimes better. There is, I think, a presupposition that the technology decreases translation quality, or there is the expectation, perhaps learned from previous teachers, that they’re not supposed to like working with machine translation. They want to give us the answer that they think we want to hear. So there’s a marked reluctance to use machine translation, or at least to confess that machine translation is being used.

I also find resistance to machine translation in translation companies in Australia, many of which don’t want to go into translation technologies because they think that machine translation will give inferior quality. Or they do it, but they don’t advertise it. They’ll advertise different technologies, but they will not mention machine translation.

For example, I was suggesting that I could do some short-term training for healthcare translators in the COVID context. The people from education within the Medical Faculty agreed that we must warn people about the dangers of machine translation. But I wanted to teach people how to work positively with machine translation. I think the message we have to get out there to society, not just to our students, is that it can be very efficient to use machine translation and fix it up. You can use machine translation with your own glossaries and your own translation memories so that the quality is actually very good. And you can gain a lot in efficiency. A few months ago we had news of COVID translations coming out eight weeks after the start texts were written. They’re not using any technology; they’re taking so long that the translations are as good as useless.

Juerong: How do students participate in online teamwork translation projects.

Anthony: Students get given a complex activity that may take as long as one and a half hours. They work in small groups. Sometimes that involves having separate roles within the task. Students are left to their own devices because in this field of translation technology, there are written instructions online, instruction videos online, and forums where users send in questions and get replies. So when students are confronting a problem, they first have to try to solve it for themselves.

If they’re really stuck, they can call for a teacher. The teacher, though, will not give them the solution – the teacher will tell them where to look for the solution. The secret in this approach is that the aim of the course is not to teach a given set of technologies, since in five years time, the current technologies will be out of date anyway. The aim is to teach students how to learn new technologies quickly, using their own resources. Once they have finished their studies and they are working for a language service provider, that company will very probably have its own software to use. So that’s the pedagogical aim: we teach how to learn technology.

Note: Translation Technologies has been granted free access to Trados and Phrase.