Nobel Prize Winners Notebooks Windows on Laboratory Life – PART I

by Katrina Dean, University Archivist

In the Melbourne winter of 1935 Frank Macfarlane Burnet, Head of the Virology Department at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (WEHI) felt himself coming down with a cold. Instead of drinking a cup of tea or going home to lie down, he took a sample of his nasal mucous and tried to establish the virus on the outside layer of a chick egg embryo. This was Burnet’s technique for growing and studying viruses that he developed as a research fellow a few years earlier at the National Institute for Medical Research in London. A model of this technique as well as Burnet’s notebook is on display at the Melbourne Museum as part of its Biomedical Breakthroughs exhibition until 22 January 2017. Burnet’s sketches in the notebook depict the replication of a cold virus and he notes the end of the experiment, contaminated by a staphylococcus bacterium. The propensity of experiments to fail, for the wrong organisms to grow, or uncertainty about what was being looked at are just a few of the practical insights into laboratory life gained from Burnet’s notebooks.

One of Melbourne’s most famous scientists, Burnet shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine with Peter Medawar for discovery of acquired immunological tolerance in 1960. Five notebooks from Burnet’s substantial archive at the University of Melbourne document his journey from the common cold to immunology. These have been digitised and are for the first time available online worldwide. Detailing experiments, summaries of research at WEHI, ideas for research and notes on epidemiology these notebooks contain unexpected glimpses of Burnet’s life from family holidays and illnesses to his notes on the international situation and its local echoes in World War Two Melbourne. They reveal not just how much the practice of science has changed in the last 80 years, but also the nature of recording science.

Seventeenth century founders of the Royal Society like Robert Boyle, John Ray and Robert Hooke transformed the humanist tradition of commonplace books containing maxims, proverbs and quotations into a long-term quest for the empirical accumulation of facts and knowledge. According to early modern historian Richard Yeo, note-taking dealt with ‘the proliferation of printed books’ also ‘assembling and securing information books did not supply’. Memory was no longer sufficient in the accumulation of knowledge so ‘they made note-taking and information science a crucial part of the modern scientific ethos’. The scientific revolution valuing empirical knowledge and its demonstration in experiments was also an information revolution.

Since this reimagining of knowledge through notes, scientific notebooks have served a wide range of purposes. They have been used to separate private from public information, detail recipes and processes, for numerical accounting, standardisation, data sharing, visualisation and cognitive modelling, as a research technique, in management and for delineating ‘investigative pathways’. Some of these uses are evident in Burnet’s notebooks. Notebooks can be messy, ugly and impenetrable, but also things of beauty.

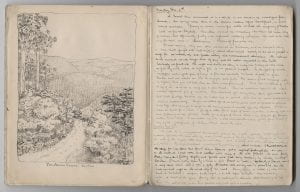

Burnet’s laboratory notebooks have a precursor in his diaries and field notebooks kept while he was a student at Ormond College at the University of Melbourne. A shy young man from country Victoria, Burnet took comfort in the Australian bush and from an early age developed and sustained a passion for beetle collecting, like nineteenth century evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin. An accomplished sketcher, these are delightful renderings of Burnet’s otherwise lonely student days, with intricate scenes of hikes in the Yarra Valley and of the specimens Burnet collected. Unsurprisingly, Burnet’s laboratory notebooks retain many elements of field notebooks identified by US ecologist and historian of field science Michael Canfield, including the diary, journal, data and catalogue, with hand-drawn illustrations. Three examples suggest a laboratory life differing in many respects from today’s and provide fascinating insights into the broader context of a Melbourne biomedical research institute between the 1930s and the 1960s.

Burnet’s attempt to culture the cold virus from a sample taken from him-self was not a one-off. His laboratory notes especially in 1935 and 1936 (1986.0107.00011) record several attempts at self-experimentation and recruitment of volunteers among the staff and associates of the Institute including Burnet, nurses, family and friends (including children) through the collection of samples and attempts at infection, inoculation, and tests of antibody production. One such episode is described in Burnet’s biography by Christopher Sexton. Early in World War Two a group of 18 medical student volunteers were taken to Rosebud on the Mornington Peninsula in Victoria and infected with non-virulent or virulent strains of influenza to study their reactions, providing Burnet with important clues about the effectiveness of virus strains cultivated on chick-egg embryos in humans and antibody production. Burnet’s main goal in this period was to develop a vaccine to protect against influenza outbreaks in the military services. He followed up with a similar experiment among 107 army volunteers at Caulfield racecourse in Melbourne in 1942. In the light of today’s protocols for clinical trials, this may seem irregular, but such experiments were not considered dangerous, unethical or biased and can be placed in a long tradition of self and volunteer experimentation in the history of science. In fact the two competing projects to sequence the human genome at the turn of the 21st century both sourced their DNA samples from scientists working on the projects.

Continues – Part II here