Germaine Greer Meets the Archivists

8 March 2017 (International Women’s Day 2017)

Kathleen Fitzpatrick Lecture Theatre, The University of Melbourne

By Rachel Tropea, Senior Research Archivist, Digital Scholarship (University of Melbourne), and Acting Deputy Archivist, University of Melbourne Archives

‘When people want to talk to me about me, I’m bored’ – Germaine Greer. ‘Once I am gone, I am yours to reinterpret’. #greerarchive #IWD2017 (the first tweet of the night by Nikki Henningham)

500 people crowded into the Kathleen Fitzpatrick Lecture Theatre, ahead of the 400 people on the waiting list, for Germaine Greer Meets the Archivists – the launch of the Germaine Greer Archive hosted by the University of Melbourne Archives (UMA). Earlier that day, Greer had arrived from the UK, headed to UMA where she had dropped off more records and held a ‘pre-match’ with the Greer archival team. This is an archive still being ‘created’.

To say most of us in the audience were excited is an understatement – we burst into applause, cheering and nearly out of our seats as the official proceedings began. UMA staff had been preparing for this, and I had been around all day to witness their nerves and excitement.

Never before has a collection at UMA generated this much public interest and anticipation. After an introduction by Professor Julie Willis, the ‘Greer Gang’ Rachel Buchanan (Curator), and archivists Sarah Brown, Kate Hodgetts, Lachlan Glanville, and Millie Weber each spoke, setting the tone for the night and framing the conversation between themselves, the archivists ‘processing’ the collection, and, the first ‘keeper’ of the records (as Greer referred to herself). “We have met many versions of Germaine and now Germaine can meet us” said Rachel Buchanan. They talked particularly of the series they had each painstakingly worked on with deep intelligence, humour and insight to an enthralled audience. It is clearly a labour of love for them.

Germaine Greer, and Christopher [her cat], have gazed down on me from our office noticeboard for the months I have spent with the archives of Professor Greer’s “Major Works”…the series reveals the interweaving of Germaine Greer’s work and her life; constantly working but with the energy and aesthetic to create environments of beauty and practicality in houses in London, rural England, Italy – even in Tulsa, Oklahoma – and returning at last to save a Queensland rainforest at Cave Creek. (Sarah Brown)

I feel deep admiration and a little jealousy over their efforts in archiving this collection – Kate listened to 150 hours of audio material, Sarah paged through 600 files about Greer’s publications, and Lachlan read 40,000 letters,

many of which are fairly routine…But interspersed are some remarkable items that drop you out of time, such as this playboy reader’s letter. Seeing the trace of a blue collar guy from Philomath Oregon, perhaps reading Playboy in his lunch break at the cannery, picking up the closest piece of paper to hand to share his thoughts on the social-sexual melodrama of male female relations to arch feminist Germaine Greer feels like an extraordinary gift. (Lachlan Granville)

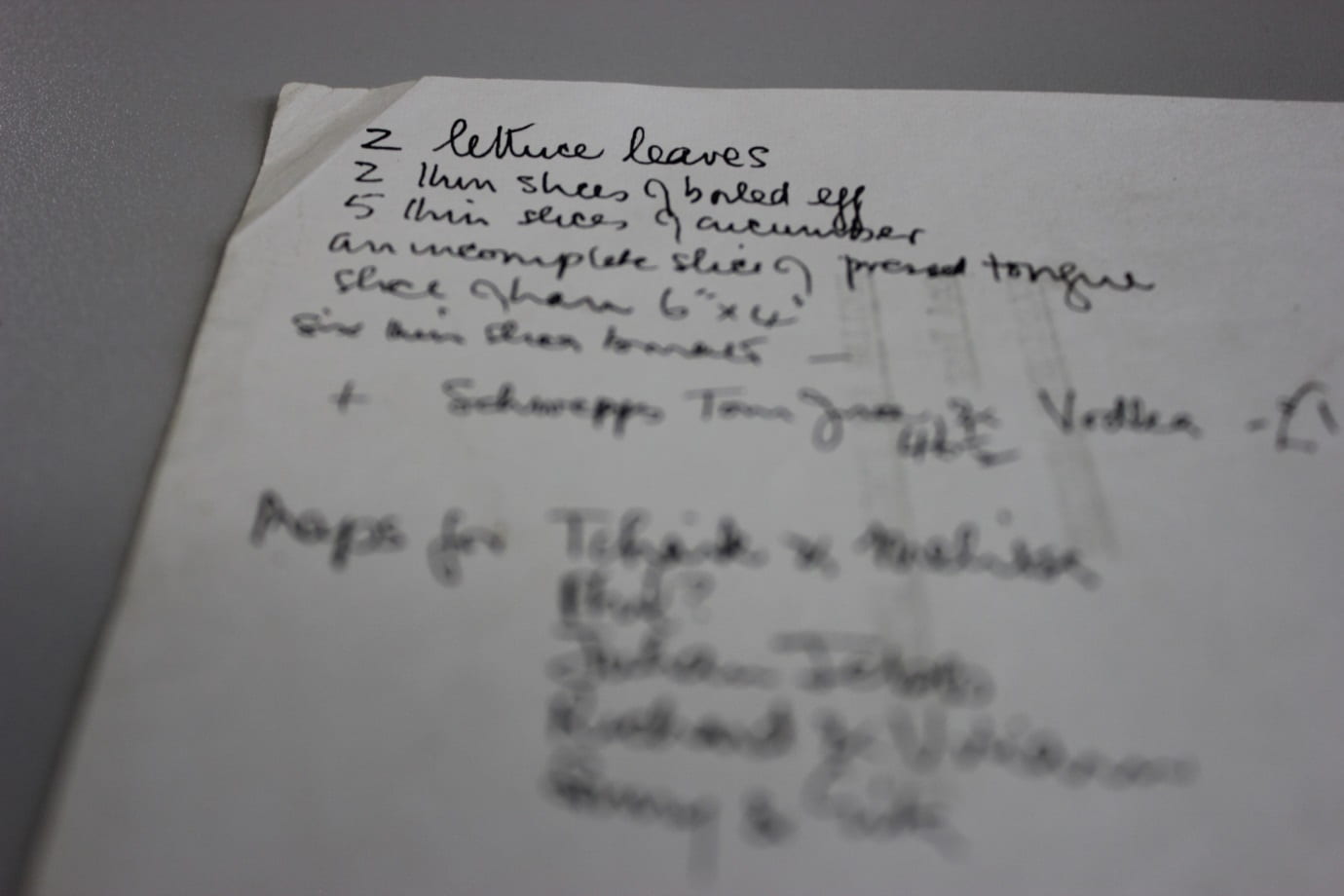

Millie who worked on the Women and Publications series described how “The blank backs of meeting minutes showcase sketches and shopping lists that…are a kind of found poetry”.

How often do we as archivists get to ‘read’ each individual item in a collection? I never have. Who has worked directly with the original keeper of the records? Not many of us. And how many people, outside of the profession, wear an archivist’s hat through their career? Greer kept the archive, very consciously from early on, referring to it in recordings:

Over the years Greer has been fully aware that she was building an archive, it was done very much with intention and there is evidence of this throughout the archive itself…At one point in an audio diary Greer gives the date and states on the recording that it will make it ‘easier for whoever gets her paws on this tape’. Being the person with ‘her paws on the tape’ I appreciate that gesture. (Kate Hodgetts)

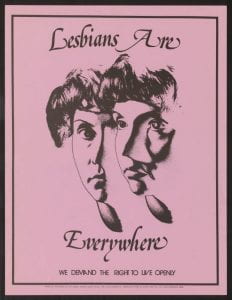

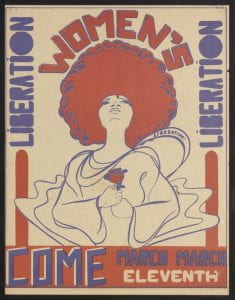

Later that night, Greer spoke of her motivation for keeping records, as evidence to counter the ‘falsification of real events… but already in an unthinking way, I’d begun to keep things. One of the most interesting things about the second wave of feminism is that it coincided with terrific creativity from young women…they were producing these little fanzines, these little magazines, that were drawn, that were photocopied, that were stapled, and I thought they were amazing’.

Greer maintains that her archive is ‘a portrait of a time…a lot of the letters that you’ll see in the archive; and to me, it touches my heart that they are entrusting me with this evidence of their feelings and their confusion and their despair very often. I suppose I think in a way that the archive is sacred, that it’s a sacred trust, and so my job was to find people that would take care of it, who would treat it with the gentleness that it deserves’.

And Greer remains consciously involved. The process of collaborating, negotiating, and the dynamics of the relationship between Greer, the Greer Gang, and the UMA Archive with its inbuilt systems and policies are complicated and occasionally fraught. Greer admitted to having mixed feelings handing over this collection, her life’s work; and, working with someone of Greer’s stature while rewarding and stimulating must be daunting at times. We archivists are most often working with the records of ‘dead’ people.

The Greer Gang shared star-billing with Germaine Greer and they are the inspiration for this post. For those of you who were not there, I am sure you will be delighted and moved by their exceptional speeches, and I encourage you to watch the recording of the night’s proceedings available online at http://events.unimelb.edu.au/recordings/1590-germaine-greer-meets-the-archivists.

I continue to be impressed by the way the Greer Gang and Germaine Greer narrated the story of the records, revering the archival process and in turn the profession, and imbued that into the audience of largely non-archivists. They showed us that the Archive is not a static thing, but rather that it can evolve; that it is not where records go to die, but a place where they can be brought to life:

I look at this wall of boxes and see a mausoleum. Or morgue. Or jail…Everything locked down and sealed off, sanitised…But if I tilt my head sideways, I see a skyscraper tipped on its side. Every box a window into a different room and each room is bursting with life’. (Rachel Buchanan)

Rachel Buchanan described the night on twitter as “an unusual, dynamic, challenging event”. An audience member wrote that it was “the most affirming and most amazing archival experience I have ever had”. The night, the speeches, the experience of this archive from various perspectives, are all part of the fascinating story of these records.

Record of the tweets about the night gathered via the hashtag #greerarchive: