Nobel Prize Winners Notebooks Windows on Laboratory Life – PART II

by Katrina Dean, University Archivist

(read Nobel Prize Winners Notebooks Windows on Laboratory Life – PART I here)

When a serious accident in Burnet’s laboratory did happen, self-experimentation was not the cause. An experienced researcher with a growing scientific reputation, Dora Lush had recently returned to Melbourne from a fellowship at the National Institute for Medical Research in London. In 1943 while inoculating animals to develop a vaccination for scrub typhus a tropical disease caused by a ricksettia (a form of bacteria) she accidently injected her-self in the hand when the needle slipped. As told in the Biomedical Breakthroughs exhibition, Lush became seriously ill and died within a few weeks. The progress of scrub typhus research is described in one of Burnet’s notebooks (1986.0107.00015). His summary for May 4th reports: ‘No advance in scrub typhus work. Miss Lush has infected finger ? due to ricksesttia. None of the strains are yet growing adequately in yolk sac.’ The June 3rd entry simply reads: ‘Miss Lush died of infection on May 20th. Williams carrying on.’

Burnet often refers to his research assistants throughout the notebooks. These were all women with whom he worked alongside individually: Margot McKie (1928-1934), Mavis Freeman (1928-1940), Dora Lush (1934-1939), Diana Bull (1941-1943), Joyce Stone (1944-1950), Patricia Lind (1944-1965), Margaret Edney (1948-1956), Margaret Gilpin (1948-1949), Margaret Holmes (1958-1965) and his daughter, Debra Burnet (1960-1962, 1963-1964). Rather than working in large groups, these scientific partnerships were part of Burnet’ ‘small’, low technology approach science in the Institute, which changed when he retired in 1965. Their experiments and observations are often mentioned in the notebooks, along with delays to a line of research because one of Burnet’s assistants is away.

Another observation is the number and variety of animals, humans and biomaterials that entered and exited the laboratory. We often think of biomedical laboratories today as being self-contained, highly secure environments. Biomedical breakthroughs are often associated with a single experimental organism, such as the geneticist’s fruit-fly Drosophila or worm C.elegans. The Howard Florey Institute for Experimental Physiology and Medicine across the road from WEHI on Royal Parade was at one time known as ‘The Sheep Hilton’. According to Sexton, Burnet collected his strains of bacteriophages (viruses infecting and replicating with bacteria) from the faeces of farm animals on his brother’s farm in Gippsland and took these with him to England when commencing his virology research fellowship at the National Institute for Medical Research in 1932. In 1933, virus research in Melbourne was given a boost when Burnet returned to WEHI with an old brown suitcase containing a collection of standard strains of viruses from the National Institute’s collection, including vaccinia, neurovaccinia, cowpox, fowlpox and canary pox viruses, and the Rockefeller strain of herpes simplex. Burnet further mentions in his notebooks parrots and human sputum (Psittacosis), monkeys (Polio), chick egg embryos (Influenza and other viruses), guinea pigs, ferrets , possums (Myxomatosis), sheep (Louping Ill), and human brain tissue. In this period, WEHI interacted widely with the outside world through the movement of biomaterials, animals and people, connected to both local and international networks of virus research.

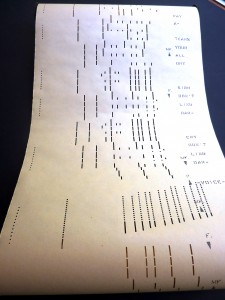

How would Burnet’s laboratory notebooks measure up today? Increasingly, standardised laboratory notebooks including electronic notebooks are being retained for scrutiny by other researchers, administrators, lawyers and commercial partners. Sharing and re-using data, research integrity and the protection of intellectual property drive these developments. The shift from private to public document implies a changed understanding of what information is relevant to include. Even in the field sciences, scientists who make this shift notice the difference. According to late US botanist Jim Reveal, who moved to a computer based notebook in 1998 ‘my mental editor says “no, that is not proper for a scientific journal”. ‘Emotions of finding something new, once mentioned in my handwritten field books, are now missing.’

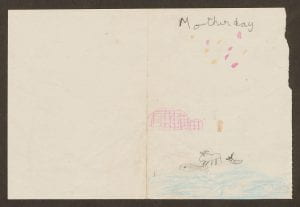

Many historical facts including the names of people working in the laboratory, details of recruitment for clinical research, animal experimentation and sourcing and use of biomaterials could likely be extracted from today’s electronic notebooks. Their juxtaposition in Burnet’s hand with sketches alongside details of his holidays, family illnesses, ideas, publication deals, current affairs and career highlights brings the page to life in a way that suggests connections and narratives, a richly decorated window on laboratory life.

After 1948, Burnet’s detailed summaries of goings on in the laboratory end. His last experiments with Margaret Holmes on autoimmune pathology in New Zealand Black Mice are documented in two laboratory notebooks dating 1960-1965 (1986.0107.00013; 1986.0107.00014). What can account for these gaps? Burnet became the Director of WEHI in 1944, so maybe he was too busy for work at the bench? Or maybe research assistants kept records that weren’t collected? Maybe laboratory notes are dispersed throughout the rest of his papers? To answer these questions, researchers would need to start with a conceptual map of his archive. At the very least, Burnet’s notebooks remind us that science is a human endeavour.

The digitised collection is available online with further details about Burnet’s notebooks and collection at the University of Melbourne Archives.