Cricket on the fore-edge: finding hidden paintings within the page-ends of books

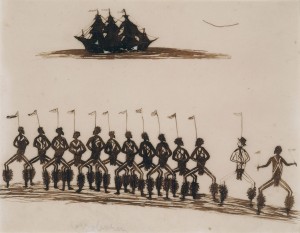

Next time you open a book from the late 18th or 19th century, take time to gently fan the pages. If you are lucky you may be surprised to find a hidden fore-edge painting lying unexpectedly within.

Fore-edge painting

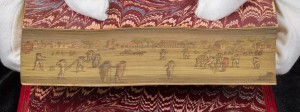

The fore-edge of a book is the long open side opposite the spine where the page edges are exposed to view, and the side from which you enter to turn the pages of the text. The painting of decorative pictures on the fore-edge of books gained momentum in the 1750s, when it became a signature device of the Halifax, Yorkshire bookbinding firm Edwards. These watercolour illustrations were applied to the book edge whilst the fanned surface was held in a brace. Once dry, the book was allowed to relax to its normal position with the fore-edge painting cleverly retreating inside, out of immediate view. The closed fore-edge was often painted over in gold pigment, to cover the residual traces of watercolour that were sometimes faintly observable.

The technique of using the fore-edge to record information on books can be traced as far back as the 900s. In modern book shelving systems, the fore-edge faces towards the back of the shelf, but in the medieval period, books were commonly shelved on their side and/or in chests, with the fore-edge facing outwards and open to view. As the heavy leather bindings were difficult to write on, the fore-edges were inscribed with the title of the book or with a rudimentary shelf mark to aid identification, in much the same way that call numbers are attached to the spines of library books today.

The technique of using the fore-edge to record information on books can be traced as far back as the 900s. In modern book shelving systems, the fore-edge faces towards the back of the shelf, but in the medieval period, books were commonly shelved on their side and/or in chests, with the fore-edge facing outwards and open to view. As the heavy leather bindings were difficult to write on, the fore-edges were inscribed with the title of the book or with a rudimentary shelf mark to aid identification, in much the same way that call numbers are attached to the spines of library books today.

Felicia Hemans and her poem, Casabianca

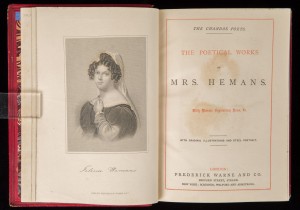

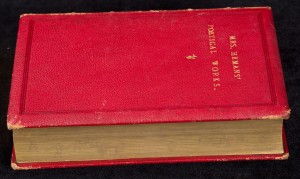

At first glance this elegant volume of poems by Felicia Hemans (1793-1835) is no different to many of similar age and provenance in the Rare Books Collection. But if you slowly splay the page edges and look again, a hidden image of a cricket field appears which did not seem to be there when the book was lying flat in its closed position. The effect is curiously captivating and you find yourself fanning the pages again to make sure, and miraculously the picture reappears!

Felicia Hemans was a prolific English poet, who spent much of her life in Wales, and whose early work gained the attention of Shelley, with whom she briefly corresponded. Her poem, Casabianca, is well known, especially for its oft repeated first line:

The boy stood on the burning deck,

Whence all but he had fled;

The flame that lit the battle’s wreck,

Shone round him o’er the dead…

The poem, which continues for another nine stanzas, tells of the heroism of a 13-year old boy, Giocante Casabianca, son of the Admiral of the Orient at the Battle of the Nile (1798). After the ship had caught fire and all guns had been abandoned, he remained at his post, and subsequently died in the tremendous explosion when the flames reached the gunpowder store.

Parodies of ‘The boy who stood on the burning deck’

On a more humorous note, the poem has also been much parodied since it was first published in 1826, including the following by English comedian Eric Morcombe (1926-1984):

The boy stood on the burning deck,

His lips were all a-quiver;

He gave a cough, his leg fell off,

And floated down the river.

And to accompany our cricketing scene, a contribution attributed to that great wit Anonymous:

The boy stood on the burning deck,

Playing a game of cricket;

The ball rolled up his trouser leg,

And hit his middle wicket.

Susan Thomas, Rare Books Curator

Bibliography & further reading:

Hemans, Felicia. The poetical works of Mrs Hemans. London : Frederick Warne, [1880?]

Weber, Carl. Fore-edge painting : a historical survey of a curious art in book decoration.

Irvington-on-Hudson, N.Y. : Harvey House, c1966.